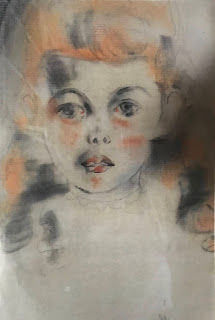

(Above, my self portrait with a photograph of the original drawing done by my grandfather, Condé)

All my life, since I wrote my first story at the age of five on paper towels taken from my school’s toilets, I defined myself as a writer, not a painter. It was a definition that I had to make in a way, as my grandfather’s vocation as a painter was the ultimate family role model. From the earliest age, the philosophy of devoting all, to ART rather than any practical pursuit of wealth or security in life, was drummed into my brain. Along with that was its corollary: ‘Art demands suffering. All great artists must suffer.’

The effect of that philosophy essentially produced a childhood and adolescence wherein my mother, rather than empathising or sympathising with any traumas I endured, patted me on the back and congratulated me for taking another beating in the service of the almighty god of Art.

I do not exaggerate here, and I loved and still love my mother, but that principle was toxic. Childhood is hard, but a good parent should lend a helping hand when a child stumbles or is struck by a blow. Acceptance of sadism as a natural even necessary agent in the creation of an artist should be repudiated.

Well, that is neither here nor there. I took up painting after I was diagnosed with breast cancer, and created my first significant oil painting after radiotherapy. It is a self portrait that was based on a portrait my grandfather did of me when I was five.

It is significant for a number of reasons. By the time I painted it, my mother was dead. The original was in one of the houses my sister and I inherited jointly as beneficiaries of the most dreadful Trust one ever could create, a surefire path to torture, given the fact that we were made co-Trustees as well, and my sister, like Sauron, does not share power with any one.

It may lack technique and skill, but it makes up for that in its unflinching honesty. It remains a record of everything that child had to endure. And the cancer and the death of my mother made a part of me a child again, a terrified little girl at a point where the world she knew suddenly lay in ruin round her.

I used to look at the original, and see the innocence of childhood there, but it was a portrait, even then, of a victim. It was, after all, when I was five that my mother divorced my father.

I never thought of that before. I simply thought of being a little girl who wanted to be a writer, who could read and loved books even at that early age. I slept on a mattress on the floor beneath a big easel in a flat that my mother and I assume my father had rented in the same building where my grandparents had a flat as well. My father and mother fought constantly, and his long absences either were the cause or the result of these borderline violent altercations. I was five. My sister was two. She emerged essentially unscarred from this marriage, as she simply was too young to have any knowledge or memory of the years when my parents actually were together.

Memories of this period are seldom good ones. My mother rewrote history to make it all appear otherwise, but here are realities I suppose I should attach to the portrait.

My Uncle Charles was an alcoholic and had a bad car accident. He came to visit, and I, never having seen any one damaged like that before, was terrified of him. His face was covered with cuts from shattered glass. He looked like a monster from a horror film, not like the Uncle I knew. So much so that his visit, coupled with my general sense of misery and apocalyptic fear, prompted me to run away from home. I had a clear destination. There was a beautiful church about half an hour’s walk from the flat that had a little play area for children that included a kitchen with a pretend cooker and pretend food and dishes. Somehow, I felt I could live there by myself and, as it was the house of God, be safe and secure.

Some one rang the police, however, and I do not think I ever reached the promised land. I was brought back to that uncomfortable world where I knew that my father no longer would be included.

My mother changed the story into some quasi-religious pilgrimage by a child who wanted to see Christ at the age of 5.

My other memories of that time are of the budgie who dashed its brains against a window, and my mother consignimg my baby blanket to the rubbish bin. Why would a parent do that to a child against her will at a very uncertain time? My mother repeatedly got rid of the things I most treasured, never ever asking for my permission or consent.

My other prized possessions were little Matchbox dinosaurs. I do not know the maker, but they individually were boxed, with a portrait of the dinosaur on the box. I did have an actual Matchbox toy as well. It was a cenent mixer.

My mother blithely gave all of these to a male cousin while I still was very young. I was heartbroken. She could be so oblivious to any one else’s psyche.

Now we come to my other significant painting. I have been struggling with it for almost two months. It began as a view of the hillsides of Umbria. Somehow, it lacked something, so I added two rivers that met in the centre. That still did not complete the landscape. I added a little cave. Still not quite right.

Last night, I realised it was not an ordinay hillside with houses, but a necropolis based on the visit to Tarquinia, and the way the Etruscans made their dead part of their lives.

So here is my Necropolis of 2020, honouring the victims of the Pandemic, even if the death or loss of some of the tombs was due to another cause.

I want people to look at this and finally acknowledge the pain and loss. I want them to be ashamed of ther attempts to lay blame somewhere, whether it is to point a finger against China, against the bats, the minks, the government of any nation, or any one or anything else.

This is Nature at her most brutal, culling this planet. If you respond with hostility towards others, or refuse to join a common cause for all humanity, then you have been weighed against the Feather and found wanting.

China was the first to suffer, but what did we do? Did we acknowledge the grief and pain of the Chinese who had lost family and friends to the virus? No, we blamed China and in doing so, neglected to arm ourselves to wage a very grim war against an enemy that is more powerful than any human being.

Then the world drifted insanely in some countries to a political agenda, to a spurious link between a virus and a political map. In doing this, we enabled hostility and magnified differences of thought to an absurd degree. In nations where the pandemic was addressed as a medical issue, and people simply obeyed the necessary dictates of science and reason, there was victory, and lives were not lost.

From the first, loss of lives in many cases were unnecessary, but humans sacrificed other humans. The way that the nursing homes became death traps comes to mind.

No comments:

Post a Comment